What is Depression and how is it maintained?

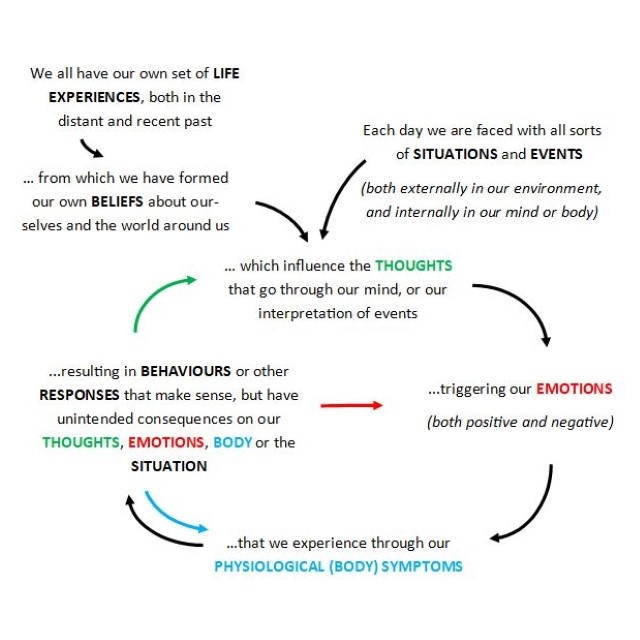

Most of us will experience periods of low mood, feelings of hopelessness, or a loss of interest or pleasure, often in response to difficult life events. We use the term Depression to describe when this persists, but is also accompanied by other symptoms, such as a loss of appetite, depleted energy, difficulties with sleep, poor concentration, feeling bad about oneself or thoughts of being better off dead. Nowadays, there are several effective treatments (both medical & psychological) for Depression, arising from a range of useful biological, psychological, or social-based theories. Cognitive Behavioural Therapies (Yes, there are several of them!) recognise the connection between neurobiology, physiology (i.e., the body) and psychological aspects of Depression, but emphasise changes in cognition (thoughts and beliefs) and behaviour that influence these other areas, to break free from the vicious cycles that maintain symptoms.

What we Think: Negative Thoughts and Beliefs

Traditional Cognitive Therapy (Aaron T. Beck, 1979) suggests that Depression is maintained by negative beliefs about oneself, the world and the future, which arise from the meanings we attribute to our early life experiences during childhood. The idea is that we then develop a set of rules or assumptions to protect ourselves, which can de-activate negative beliefs until they are reactivated by ‘critical incidents’ – recent life events to which we attribute similar meanings. For example, growing up in a family that placed value on achievement, I may have I perceived myself to fall short on occasion, concluding in those moments that I was a failure. However, by developing the rule ‘If I always keep on top of things, then I am good enough’, I could feel okay about myself. Until perhaps I became a parent, and it was no longer possible to maintain such standards. In fact, I may start to try even harder and raise the bar to prove that I am good enough, leading to exhaustion and a constant sense of not meeting my own expectations. In CBT, we understand the day-to-day thoughts and images that go through our minds to reflect our underlying beliefs, so in this case I would be likely to be highly self-critical and perceive any incomplete task or imperfect result as a sign of failure, providing further evidence. We often don’t pay too much attention to such ‘automatic’ thoughts, and simply take them as truths, which can be an important vicious cycle in Depression.

What we Do: Avoidance, Withdrawal & Other Responses

When the black cloud of depression descends on a person, the simplest of everyday tasks can take a tremendous amount of effort. Despite this, I find that people are often highly critical of themselves for struggling to maintain previous levels of activity or social connection. Oftentimes, the most distressing thing can be feelings of helplessness due to not benefitting from pushing oneself to engage or try different activities. In CBT, we work together to analyse and test the unintended consequences of our natural responses to depressive symptoms, but also try to understand how our perception of such difficulties can in turn influence our thoughts and beliefs.

How we Think & Do: The Vicious Cycle of Rumination

More recent research into features of Depression, particularly those factors influencing poorer outcomes from psychological treatments, emphasises thinking processes such as ‘Rumination’. With its linguistic origins in the Latin for a cow’s digestive system, or chewing the cud, in psychological terms Rumination describes repetitive negative thinking or dwelling on the meaning, causes or consequences of events. In Depression, this can often involve thinking about memories of past events, which are simply retrieved more readily from memory when we are depressed, or when our negative beliefs are activated. Alternatively, this could involve continually asking ‘why?’ in terms of current problems, particularly trying to understand ‘why am I feeling this way?’. To illustrate, perhaps imagine how it might feel to spend the next hour dwelling on all your past mistakes and failures or trying to answer unanswerable questions in your head such as ‘what is my real purpose in life?’ (I have tested this myself, but I expect you can guess the results!). In CBT, we can explore your personal experience of depression to develop a detailed understanding of how such thinking processes might interfere with normal activities to maintain negative beliefs or influence emotions, body symptoms and behaviours, to identify individualised solutions to break the vicious cycle.

So, how can CBT help?

You would be right in thinking that there is a lot more to learn about CBT for Depression, and certainly many experts have written entire books that vary widely in their content and approach. In this blog I have included a few common examples of how CBT might help you to understand the development and maintenance of Depression, so you can work together with your therapist to break the vicious cycles. In practice, this could involve any of a wide range of techniques, both within and between sessions, that seek to increase our awareness, test our beliefs to develop new alternative perspectives, breakdown steps to actively pursue valued goals, or perhaps re-process distressing memories to update their meanings so that you can break free from the past.